The tragic events unfolding in Ohio are an important reminder of some of the dangers of the existing chemical industry. Since the chemical railcar accident in early February, we’ve read harrowing stories of dead wildlife, people getting sick, and water contamination, among others. It’s difficult this early on to know what is real and what is being sensationalized in this age of social media. What we know without a doubt is that an environmental catastrophe is occurring that will negatively affect this area and surrounding states for generations to come.

What many didn’t realize prior to this disaster is that it is commonplace to ship large rail cars full of hazardous materials through cities and residential areas. The question is whether society should continue to accept this reality, or look towards technological innovation that offers a more sustainable future. And we know it can be done—there are numerous examples of dangerous goods industry has largely phased out shipping of due to the risks. This practice can be extended to other materials.

Much like how our food system has been industrialized for increased efficiency and mass production with large dairy and factory farms, today’s chemical industry is centralized in hubs like the U.S. Gulf Coast. This allows chemical producers to build large manufacturing plants to minimize cost of production, and then ship those chemicals to where the consumers are.

Low-cost chemicals and plastics helped propel society forward in the second half of the 20th century in more ways than most of the general public knows. These are the basic building blocks of many goods we use every day, like cleaners, shampoos, phones, cars, and airplanes.

Centralized mass production was developed by very smart people with the best of intentions. Unfortunately, we are starting to learn about the environmental downsides of these practices, and how they are not sustainable for the planet going forward.

The word “chemical” often has a negative connotation, but many of the chemicals that are produced are not hazardous or are mildly hazardous, and can be managed with standard controls. It’s important to focus attention on hazardous chemicals, and the ways we can reimagine how they interact with society.

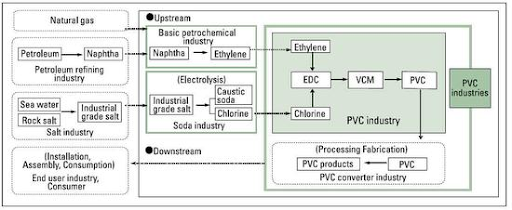

For example, Vinyl Chloride Monomer (VCM) is an important building block chemical used for making PVC (polyvinyl chloride) pipes and many other goods we buy everyday. PVC is one of the most largely produced polymers in the world, all of which is made from VCM. PVC itself is not dangerous or harmful to humans. One of the modern marvels of chemistry is how a very dangerous molecule like VCM can be converted to a very safe molecule like PVC in just a few steps.

Over 50 million metric tons of VCM and PVC are produced worldwide each year. VCM is often converted into a PVC resin, which is then sold and shipped to customers to produce the PVC pipe or other final PVC product. Sometimes though, the VCM is sold and shipped as-is and the customer converts VCM to PVC themselves. VCM is a known carcinogen and mutagen, which causes reproductive damage. It severely irritates the skin, eyes, nose, throat, and lungs and should be handled with “extreme caution” according to the EPA. As a society we have to ask ourselves, “if it’s possible to ship a safe PVC resin around the world instead of a hazardous VCM chemical, shouldn’t we be doing that all the time?”

Shipping of these chemicals in the US is regulated by the DOT (Department of Transportation) with a special program called HazMat (hazardous materials). This program lists specific requirements for how to transport these chemicals to ensure safe handling and identification.

There are a few chemicals listed on DOT’s forbidden materials list, which are mostly related to explosives. Most common chemicals that are carcinogens and mutagens are not on the forbidden materials list. This is especially concerning for shipping via railcars, because the rail system in the US was originally designed for passenger transport, and thus often goes through cities and residential areas.

Not commonly known is that the US has the largest rail transport network in the world—40% larger than China’s—and most of it is for freight rather than passengers.

Lots of railcar shipments of chemicals means lots of opportunity for accidents to happen, and one the likelihood of dangerous accidents in a railcar is higher than inside a chemical production facility that has multiple lines of defense. It only takes one bad wheel bearing to derail a train containing 150 railcars. If just one of those railcars contains a toxic chemical, environmental catastrophes are possible.

Accidents are rare considering how widespread shipping of these types of materials are, but when accidents do happen, the effects on the environment are severe. One common practice for minimizing the risks associated with these chemical accidents is completing a “controlled burn.” This reduces the explosion and contamination potential, but this is only the best of many other bad options. In this case, while completing the controlled burn of Vinyl Chloride, phosgene gas and hydrochloric acid are released. Phosgene gas is heavier than air, so when it releases into the atmosphere it stays low to the ground, maximizing its dangerous impact to people and the environment.

Solugen is working hard towards a better way to bring chemistry to life for future generations, with the help of biology. By combining the best of these two fundamental scientific fields, society can unlock a safer and more sustainable way to produce and deliver important chemical building blocks. Cell-free enzymatic pathways can be engineered for high yield and precision in a single reaction complex, allowing for smaller-scale manufacturing with lower capital requirements.

This can enable a decentralized distribution model that minimizes risk and carbon emissions required for transportation. “Farm-to-table” is an emerging trend for the food industry that we can look to for inspiration, where the food tastes better because it is fresher, more sustainable for the planet, and more humane for all living things. Today, it generally costs more to produce, but a dedicated focus on innovation will drive it to cost parity. Chemicals and materials can also follow this operating model.

VCM to PVC offers a great example of this concept. A mini-mill that safely and economically converts the raw material ingredients of this process to make VCM is integrated onsite with the PVC pipe producer so that the existence of VCM is minimized to seconds instead of weeks.

Furthermore, some upstream materials like ethylene can be made from renewable ethanol, either from corn or from waste. And the technology to do this exists today—it’s not science fiction.

With a “do no harm” value at the core of its mission, Solugen is reimagining the chemistry of everyday life. And we’re on the front lines of safer chemicals because we want to make sure accidents like the Ohio train derailment never put communities at risk again. Because we know it’s possible, and because humanity deserves better solutions.